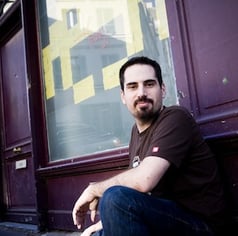

We all know that open source is critical to data science, but we wanted to learn more about the process of creating these tools and the motivation driving the impressive people building them. Most of these developers contribute for free, because they believe in the good of the project. To get the inside scoop on open source, we talked to Olivier Grisel, a full-time open source developer and one of the core contributors behind the scikit-learn project, one of the most popular machine learning libraries in the world. We use scikit-learn a lot, and try to help support the project, but as Olivier explains, open source isn't a perfect system.

We all know that open source is critical to data science, but we wanted to learn more about the process of creating these tools and the motivation driving the impressive people building them. Most of these developers contribute for free, because they believe in the good of the project. To get the inside scoop on open source, we talked to Olivier Grisel, a full-time open source developer and one of the core contributors behind the scikit-learn project, one of the most popular machine learning libraries in the world. We use scikit-learn a lot, and try to help support the project, but as Olivier explains, open source isn't a perfect system.

Claire Carroll: As someone who's really involved with open source, what does a normal day look like for you?

Olivier Grisel: I've been working at Inria for the past five years. I'm embedded in a research team that does brain data analysis. But most of my colleagues are more on the scientific side of operations. And so they are Ph.D. students, post docs, and researchers working on this kind of data. My own job is specifically to work on the open source stack, scikit-learn in particular.

So what I do is I look at GitHub, I see the pull requests that I've been working on recently, I review what progress they've made during my last connection because we tend to work asynchronously: there are contributors from everywhere around the world. I work a lot in collaboration with colleagues at Inria but there are also people who I only work with via GitHub, sometimes I interact with them just once during the time required to address a specific bug report or review a pull request. There are also other people that I know more personally. We check in on a regular basis via video call and we do pair programming this way.

CC: Zooming out a little bit, why do you think that open source is important and why are you so committed to it?

OG: I think open source is important to bring a baseline of sanity. It's especially important for machine learning, data science, and scientific applications because it brings transparency which is very important for the scientific process. If you want to do good science, it needs to be open science, the code needs to be open source, the data needs to be open data, and the publication needs to be open-access so that the scientific workflow is more fluid. Open source makes it easier to reproduce published results and enables you to build upon them without starting from scratch and facing similar implementation bugs over and over again.

I think open source is also important for teaching because it is much more natural from an operational point of view. It's much easier to teach with open source tools because everybody can install them very quickly. There are no financial constraints. There are no organizational constraints with license management. And, furthermore, it gives a lot of freedom for the students to dive into the code and see implementation details and realize that nothing is magic. So if the people really want to know how it works under the hood, open source code is a very good educational resource.

Open source is also interesting to streamline the collaborations and partnerships between businesses. It makes collaboration much more efficient because it removes a lot of legal overhead. The technical people can talk to one another directly as long as they are allowed to contribute to a specific open-source project. And then they can directly discuss technical matters without having to deal with the IP concerns for each individual contribution.

So decisions can be purely about how to make the tech work the best from a user experience, computational, or statistical point of view without having to deal with a particular commercial deadline. The only focus is on making the product work better and that's it. Open source makes things work better from a technical point of view. That's one of the reasons why Linux is so successful in a corporate environment and deployed everywhere, even as a core component for mobile phones nowadays. Because it makes it possible for many organizations to collaborate and build software products more quickly by reusing existing components efficiently.

CC: It sounds like you're definitely trying to get more resources for scikit-learn. How is the balance for you, between your commitment and the lack of actual concrete resources or oversight structure?

OG: The lack of resources is not completely blocking, it's just that we have a backlog of contributors and it's a shame that we're not reviewing their work. The more resources we have, the more lively the project is and the more happiness there is. But, we're not going to die without that, at least not in the short term. I think if the project dies, it would be because of a lack of interest, which is not the case. To find resources in the past, we were quite happy with the fact that Inria has hired several generations of engineers like me and supported researchers and Ph.D. students to also work part-time on open source project like scikit-learn.

There are also public funds for research, and we allocate some of that money to support open source development. My team leaders are very sensitive to this and they make evangelism efforts so that they were able to fund engineering positions. It's easier nowadays than it used to be. In academia, there is a real fight to make it clear that investing in software tools was important for scientific progress and researchers should not only be evaluated on the papers they publish, but also on the scientific software ecosystems they sustain.

In Australia, the University of Sydney hires Joel Nothman who is one of the core maintainers. Similarly, Andreas Mueller at the University of Columbia secured significant funding to hire several core contributors to work on scikit-learn. I think it's not necessarily easy, but it's possible. However, I'm not one who is writing the grant applications, so I don't know exactly how much time, effort, and possibly frustration they involve.

When we decided to start the foundation, we had contacts with several people. And Dataiku is one of these organizations. The value of the project was well recognized by technical leaders in these different organizations, and they could convince their managers that it was a good idea to invest in the sustainability of this project.But, of course, compared to the number of organizations that use scikit-learn, only a small fraction of them give back to financially support the development. But this is the start of this process, so maybe in the future, the funding will increase. I don't know. I can only hope so.

CC: I have a little bit of an abstract question if you're willing to bear with me. Do you think there is anything we can learn from the open source consensus and surrounding framework about democracy, or ways of making decisions?

OG: If lawmakers could use a version control system, we could more easily see the “diff” and that would bring some transparency to the lineage of our laws. It's a bit of a joke, but this process could maybe be improved via tooling.

More generally, I think we should not put too much emphasis on open source as a model because it's not necessarily working so well. Open source is often marketed as, "it's a meritocracy, everyone's is on the same level and only the best decisions will be implemented." But it's actually implicitly restricted to the people that have the economic freedom to contribute because they come from a social background that allows them to do that in their spare time. I think a significant number of projects are started by students that receive help from their parents so that they don’t have to take a part-time job to pay for tuition. The open source collaboration process is only a biased kind of democracy. It's mostly privileged people who do open source in the first place, so we should not make a democracy follow that model. It's not that easy to make the open source model more democratic, knowing the barrier to entry.

CC: In addition to scikit-learn, what are you working on now, what's exciting to you? Are you working on any other open source platforms?

OG: I've been working a bit with the wider Python and data ecosystem. For instance, I've been playing and contributing a bit to the Dask distributed computation environment. Dask can be seen as an alternative to Spark; it's young, it's less well-known, and less deployed. What I like about Dask is that it’s pure Python. It's quite easy to dive into the code if you want to learn how it works and improve it. I really like this distributed community of the Dask developers: many of them are part of a project called Pangeo, where they've built a platform on top of Dask and a generalization of Pandas for n-dimensional data frames called xarray. If you work with geoscience data, for instance, you have data with different indexed axis like time, latitude and longitude, altitude, and for each cell in that volume you can store values such a the humidity level, temperature, and so forth. So it's a kind of globe-shaped data frame. Thanks to Dask, this data structure can be partitioned on several machines so as to distribute the computation and run execution in parallel.

The Pangeo project members have worked together to deploy computational geoscience environments on the public cloud with Kubernetes or on High-Performance Computing infrastructure. There are also people with a UX background. For instance, some Jupyter and Jupyter Hub developers also work to improve the interactive user interface on Pangeo. The ecosystem they are building is impressive. There are climate and HPC scientists from North America and Europe, from the Met Office in the UK, weather/forecast people, and people from Anaconda and other open source projects. The progress is really interesting to follow, and they already have good results.

For instance, they publish notebooks where you can reproduce standard data analysis pipelines starting with the raw data of ocean elevations collected with satellites by European and American scientific agencies and subsequently made available on the public cloud. The code included in the notebook can then compute the evolution over time of the average elevation of the oceans and visualize it as a world map and a curve in just a couple of seconds or minutes. It’s possible to effectively work interactively with hundred or even thousands of CPUs in the cloud. Computational science can be well improved by setting up this kind of collaborative platform.