Astronomy’s approach to data has drastically changed over the past two decades. From improved data collection methods to ML-based analytics, astronomers have more access to data than ever before.

A couple of weeks ago, I attended the Astronomical Data Analysis Software & Systems (ADASS) Conference in Maryland, and got to talk to the astronomers actually leading this data revolution. Speaking to them firsthand about their strengths and pain points, this is my summary of the current state of data in astronomy.

All of the Sky, Open to All of the People

Astronomical data collection used to be heterogeneous, relying on individual astronomers to request telescopes and record parts of the sky particular to their research. Fast forward 20 years, and efforts such as the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS), Pan-STARRS, and Large Synoptic Survey Telescope (LSST) have shifted from individualized data collection to studying larger portions of the skies and wider ranges of wavelengths of light; collecting data on more events, objects, and touching more corners of the sky through larger telescopes and better light detectors. These sky surveys are then made open to the public, allowing for astronomers all across the globe to access the data in its entirety (for free!).

Astronomers benefit from these telescopes worldwide, as they reduce the amount of individual resources necessary to participate in research, and build more time for data analysis as opposed to collection. Observing predetermined areas of the sky at consistent intervals and varied wavelengths helps astronomers distinguish common events from anomalies, and build out a more comprehensive image of our skies.

The exponential increase in the amount and standardization of public data provides an ideal opportunity for AI and machine learning to help sift through noise. Astronomers are now building models to measure galaxy morphologies using image classification, classify exoplanets using convolutional neural networks on light curves, and locate the most distant quasar to date using Bayesian analysis. ALMA Labs in Chile is currently using Dataiku (as part of the academic partner program) to build models for operations research, monitoring and predicting wear on their telescopes. As we’ve seen in other fields, the possibilities are endless.

Astronomical Data Leads to Astronomical Problems

While these collection methods have provided enormous potential for astronomers, they have also presented a number of infrastructural roadblocks:

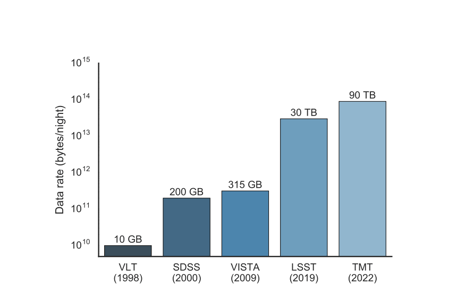

- With some of these telescope collecting up to 30 terabytes of data every night (such as the LSST), astronomers are wrestling with more than 100-200 Petabytes of extremely noisy data annually, requiring enormous storage infrastructures, as well as making global data transfer and unified access a nightmare.

- On top of this, multi-messenger astrophysics still lacks universal standards for data collection, processing, and labelling of data, creating silos that block easy data integration. To clean it, astronomers are then writing their own open source software pipelines, which is great because it gives the public access to their work, but makes it more difficult to share tools across telescopes due to the major structural differences across telescopes.

A New Frontier

The new wave of astronomical data has the ability to transform not only our understanding of our skies, but also the methods our astronomers use to actually do their research. However, while astronomers benefit from increased sharing and access to their data, they still struggle from highly siloed data collection methods, greatly delaying the analytics process.

With telescopic capabilities becoming even more impressive (such as the Square Kilometer Array [SKA] that will collect hundreds of terabytes every second), multi-messenger astrophysicists are pushing for greater systems of communication across observatories, and new universal standards in the collection process.