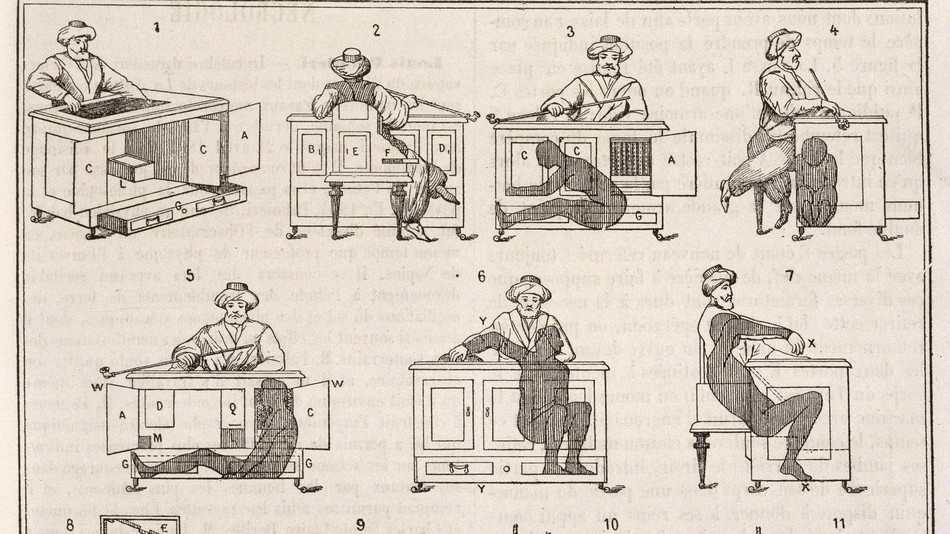

The Mechanical Turk is an old story about a fake mechanical turk that amazed people in the 18th century. The Turk was a human-sized chess player sitting near a cabinet with a chess-board on top of it. And for years, The Turk was exhibited as an automaton, playing chess against players from all over the world.

Obviously, The Turk was a very elaborate hoax with a human player inside of it, able to play the game himself/herself through crafted moves inside the closet. But The Turk really was a sensation, attracting interest from all the celebrities of the time. The Turk owner was probably on a permanent roadshow across Europe and the Americas, and it is known to have played against (and defeated!) Benjamin Franklin and Napoleon Bonaparte.

According to some accounts, Napoleon tried to play a few of his games against The Turk by cheating — that is, making illegal moves and doing petty things test the machine (typical French). Napoleon also allegedly tried to blind The Turk with a scarf and put a magnet on the board. He was probably trying figure out how the thing worked, and it’s funny to realize how foolish one looks attempting to understand how a machine works when you don’t have the modern knowledge of computer science.

But for sure, The Turk was really something important back then. If there had been Venture Capitalists back in the 18th century, The Turk could have probably raised money (and maybe even turned into a unicorn).

AI Today Has Mechanical Turk Syndrome

Today, Artificial Intelligence (AI) means looking for the magic automation. But are we still stuck at only appearances instead of what automation really is? There are certainly some signs that the market for machine-based intelligence is still in its infancy, especially in terms of its understanding by the general public.

First, the articles about AI that make it to the mainstream media are usually those about a machine defeating a human. Like The Turk, but for real. These days, the two most popular feats are the AlphaGo machine (the first machine that beat a human at real-sized Go) and the bot by OpenAI that can beat human players at Dota 2.

What these two examples have in common is that they don’t actually operate in real life, but in the fantasy universe of a game. Why? It’s because in order to learn, these systems need a very large number of examples — far larger than anything they could do in real life.

The Dota2 bot is virtually playing hundreds of years of games every single day against itself. In the meantime, it takes around 10 hours for a human to learn to play Dota2. So, as of today, AI thrives in the fantasy world where — unlike the real world — you can have it wrong often enough to learn quickly from mistakes.

Another sign of AI’s infancy is the nascent global understanding of how or why machine learning really works (even sometimes among the scientific experts in the domain. A famous 2016 paper, Understanding Deep Learning Requires Rethinking Generalization, started to spur some thoughts on deep learning — even if it works in practice, the underlying mechanisms were (and still are to some extent) not clear to people.

(In fact, the key is generalization, which for a machine learning system relates to its ability to learn key concepts from individual examples. The opposite of generalizing is memorization; like a smart donkey, a memorizing system just learns all the examples by heart without taking anything out of it.)

Because of our relative lack of maturity in terms of understanding AI, we are potential subjects to light versions of The Turk. A modern Turk wouldn’t be a complete hoax, obviously. But it could take place in a more subtle fashion, with systems that generalizes a little (but not that much) and that still require a human behind the curtains for any subtle tasks.

A sign of the modern AI Turk is that a fair number of “AI” startups are actually not implementing AI. As pointed out by this article in The Guardian about pseudo-AI, some companies run “bots” to do, let’s say, customer service. Yet in reality, under the hood, these “bots” are actually run by humans. That is, you think you’re interacting with a machine, but in fact, someone in another country is behind the keyboard answering your questions about the price of an item or giving you fashion suggestions.

Some would point out that a certain level of “fakeness” is required to make AI advance. Like the Dota2 example, you can’t make an AI work without a fair number of examples. And you can’t get those examples without having existing, let’s say, human-human interactions examples before getting to human-robot examples.

Others point out, more cynically, that we want to believe in AI: some interactions are easier if you have the impression that you’re not talking to a human, because you could feel less ashamed and more open minded. Maybe as a whole, it feels easier to be helped by a bot as opposed to someone far away in a emergent country who is getting paid very low wages — it’s AI if you want it to be.

From The Turk to Real AI

So what’s next beyond the veil of AIppearances? It took two hundred years after The Turk to create Deep Blue, the world champion chess player by IBM. Will it take us two hundred years to create real AI? Or just twenty ?

Napoleon, when trying to understand the Turk, looked like half a fool to us because of his lack of basic understanding on how a real automaton would work. Will we also look like fools from the perspective of our grandchildren because of our lack of understanding of how real AI will work?

Don’t get me wrong: appearances are important, not to mention useful. They are actually, in many cases, what keep us trying. Most of us (that is, people in the AI field) are just following the path of least resistance — trying to get AI to work in the fantasy world because that’s the most obvious entry point to arrive at techniques that would work in the real one. And we need to be positive and passionate about AI to get the proper funding that it needs.

At some point, AI will manage the nuclear plant, optimize a company budget, and setup a layoff plan. At that point, and that point only, we need to be sure most of us have the eyes and wisdom not to be fooled and see the man inside the machine.